A theological culture of belonging in the Uniting Church in Australia can and should be cultivated considering our prescribed identity as a multicultural church. In 1985, the fourth Assembly declared we are a multicultural Church acknowledging “the fact that the Uniting Church unites not only three former denominations, but also Christians of many cultures and ethnic origins.”1 This statement quotes part of paragraph 2 of the Basis of Union: The Uniting Church “believes that Christians in Australia are called to bear witness to a unity of faith and life in Christ which transcends cultural and economic, national and racial boundaries.”

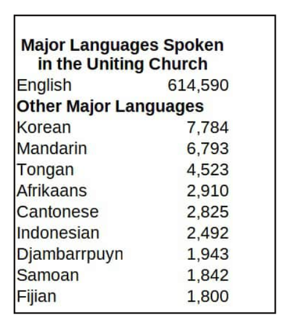

Today in the Uniting Church we worship in 30 languages other than English (not including Indigenous languages); we have more than 200 people groups who worship in a language other than English; and we have 12 national conferences that support congregations and communities of the same culture.

Yet, we have to admit that we have not become “a Church which is culturally and linguistically diverse at its core – not essentially British with add-ons from other cultures”.2

Are We a Multicultural Church?

According to NCLS standards, the Uniting Church is not considered as a “multicultural church” where no one ethnic group accounts for 80% or more of the membership. The 2021 National Church Life Survey (NCLS) found that of the 37% of church attenders who were born overseas, 28% were born in a non-English speaking country. Nevertheless, compared to other churches or the general population, the Uniting Church has a small proportion of its people born overseas. While 86% of the Uniting Church members were born in Australia, only 8.1% were born in non-English speaking countries (Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics 2021 Census data). The proportion of immigrants in the Uniting Church has increased a little over recent years,3 but many of them have come from the United Kingdom. This pattern has not changed since the time of the Federation in 1901. The precursors of the Uniting Church, the people who identified with Congregationalists, Methodists, and Presbyterians, came from the United Kingdom; The Presbyterian church was the major denomination in Scotland; The Methodists has become the major denomination in England; The Congregationalist Church was also a significant size in England.4 We, the Uniting Church, are still predominantly a Church of British origin. While Australia is one of the most multicultural nations in the world, second only to Luxembourg,5 the Uniting Church congregations still lag far behind their neighbourhoods and other community institutions in reflecting cultural diversity within the life of the Church.

In another Assembly statement, One Body, many members – Living faith and life cross-culturally, adopted by the 13th Assembly in 2012, it is acknowledged that the 1985 declaration, We are a Multicultural Church, and its recommendations in the day-to-day life, the structures and process of the Uniting Church have not yet been taken up in a comprehensive way across the local, regional, and national life of the UCA.6

Freeing the Church from Captivity to “Whiteness”

We are a theologically diverse Church: Catholic/Anglo-Catholic (14%), Evangelical/Reformed (21%), Liberal/Progressive (23%), and none of these (36%).7 But arguably our theological culture is still predominantly shaped by Western, Anglo-centric Whiteness,8 in our institutions, practices, texts, governance, and daily life itself. As Willie Jennings points out in his book, After Whiteness, “whiteness” does not refer to white people, people of European descent, but to “a way of being in the world and seeing the world that forms” a set of theological culture, systems and practices informed by coloniality, white Eurocentric hegemony and supremacy, self-sufficiency, and control.9 This argument can be supported by the lived experiences of our culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) members and communities.10 At a presbytery meeting, one of my colleagues shared a very sobering story about the place of CALD congregations within the life of the Uniting Church:

Two things I am always afraid of: being a stranger in a foreign land and being in a building that is going to fall. Before I came to Australia on a permanent visa, I was a Refugee in Egypt with no rights or privileges. And before I became a Minister with an English-speaking congregation in my current placement, God called me to start a church for an African background people in the Northern Suburbs. Finding a permanent place of worship was an issue until we had the privilege to take over that old building from an English-speaking congregation who decided to close. Every time I walk in, I have a fear that this building might fall on us, the wall is moving out and the ceilings are falling. The feeling of insecurity was real.

In a report to a presbytery by an external consultant, it was found that:

The CALD congregations struggle with the idea that they are perceived as one group, when in fact they represent diverse cultures, ethnicities, theological beliefs and behaviour. At the same time, they feel unity in being seen as “other” or different from the other congregations. They share a feeling that their communities and members are treated as “second-class citizens within the Presbytery” and they are conscious of a strong distance from the other congregations, even though their experiences and challenges may, in fact, have much in common with those communities who themselves deal with issues of nostalgia for a past time, or see themselves as having a responsibility to protect cultural standards which may have been more common some time ago. The sharing of buildings is difficult and contentious. It is a painful point that the non-CALD congregations “own” the buildings and can sometimes treat the CALD congregations as tenants. While the CALD congregations express a strong allegiance to the Uniting Church and the Presbytery, there is a breakdown in the teamwork and sense of unity with other local congregations.

The Lived Experiences of the Asymmetrical Intercultural Relationships

This is my own experience. After attending an Intercultural Service of Celebration held by a Synod in 2015 in which ten languages were used for the liturgy and the songs of six nations were sung for praise, one member of the Korean congregation asked me a bitter question: “Is this service for God, or for Anglo people who are entertained by songs and dances performed by us?” Multicultural celebrations with music, dance, and food play a certain role in recognising cultural diversity, but they seldom require genuine engagement with cultural differences and theological reflection. Deep engagement (below the cultural iceberg) comes when we are willing to move beyond our comfort zones, become aware of other ways of doing theology, and rid ourselves of our ethnocentrism. Very often we are “cultural consumers” rather than “cultural learners.”

One of the most painful experiences I have had was to witness a Korean congregation that was then six years old and growing to over 100 members leave the Uniting Church due to the lack of theological conversation and intercultural understanding. In their eyes, the Uniting Church is “liberal” and even “heretical” in that it intends to acknowledge the redefinition of marriage “outside God’s order of creation.” And they misinterpreted the Revised Preamble to the Constitution to be committing what they call “spiritual adultery” with the non-Christian rituals of the First People accepted and acknowledged in the context of Christian tradition. In my recollection, they had not been informed about the theological rationale and educational resources for the UCA’s Covenant with the Uniting Aboriginal and Islander Christian Congress (UAICC) and its Revised Preamble by their Presbytery. Rather, what they heard from the Presbytery minister was, that if they wanted to leave the Uniting Church, they should leave the premises along with their possessions including Sunday school materials and funds in their bank account!

This “liberal” image of the UCA has prevented many second-generation Korean-Aussies from pursuing their theological studies at the Uniting Church theological colleges. We, the Uniting Church, value an informed faith and scholarly interpreters of Scripture as stated in the Basis of Union (Para. 11). We seek to embrace theological richness and difference and provide ministry and leadership training appropriate to its diversity as stated in “One Body, Many Members” document. However, there are significant gaps between statements/resolutions of the Church and lived experiences/ realities of the local congregational life.11

Towards a Theological Culture of Belonging

To be a truly multicultural,12 cross-cultural,13 and intercultural14 church—a culturally and linguistically diverse church at its core, there is a pressing need to cultivate a culture of belonging and cultural humility. It is a way to engage people and groups across cultural differences while understanding and acknowledging systems of whiteness, a commitment to self-evaluation and self-critique, and seeking partnerships with people and groups working to eradicate power differentials at the systemic level. Paying particular attention to the asymmetries of power in the ”intercultural relationships” can go a long way in helping the Uniting Church cultivate a theological culture of belonging. Interweaving her Aboriginal stories with Christian stories from her own cultural and linguistic heritage, Rev Dr Auntie Denise Champion, Aboriginal theologian in Residence at the Uniting College for Leadership and Theology, teaches us a practical theology of belonging saying that:

We are being presented, both First and Second Peoples with the opportunity to follow a new path that reconciles and heals. To do that we need to be able to sing together, dance together, sit down together, eat together, learn to live together in peace, and tell stories, allowing this land speak to us and through us.15

When we practice this theology of belonging together, we can reaffirm that the Uniting Church belongs to the people of God “from every nation, from all tribes and peoples and languages” (Revelation 7: 9) on the way to the promised end which is reconciliation and renewal for the whole creation (The Basis of Union, para 3 and 18).

Footnotes

- We are a multicultural church: Assembly statement (1985). UCA Assembly, accessed 31/10/2023, https://ucaassembly.recollect.net.au/nodes/view/494. ↩︎

- Andrew Dutney, “CALLED TO OUR DIVERSITY,” Crosslight, JUNE 21, 2015. https://crosslight.org.au/2015/06/21/called-to-our-diversity/, accessed December 2021. ↩︎

- 6367 immigrants were recorded by the census as arriving in Australia between 2017 and 2021 and identifying with the Uniting Church in 2021. Cf. Christian Research Association. (2022). Australia’s religious and non-religious profiles: analysis of the 2021 census data, Christian Research Association, p. 122. ↩︎

- Ibid, p. 120. ↩︎

- Source: OECD, International migration database, 2022. ↩︎

- One body, many members: living faith and life cross-culturally (2012), UCA Assembly, accessed 31/10/2023, https://ucaassembly.recollect.net.au/nodes/view/416. ↩︎

- NCLS 2021. Denominational Church Life Profile for Uniting Church, p. 18. ↩︎

- Jennings, W. J. (2020). After Whiteness: An Education in Belonging (Ser. Theological education between the times). William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ↩︎

- Jennings, W. J. (2020). After Whiteness: An Education in Belonging (Ser. Theological education between the times). William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. “White self-sufficient masculinity is not first a person or a people; it is a way of organizing life with ideas and forming a persona that distorts identity and strangles the possibilities of dense life together” (p. 13). ↩︎

- I should note that there are some good stories of the intercultural relationships in the Uniting Church. Cf. Richmond, H., Yang, M. D., & Uniting Church in Australia. (2006). Crossing borders: shaping faith, ministry and identity in multicultural Australia. UCA Assembly & NSW Board of Missions. Richmond, H., & Uniting Church in Australia. Multicultural and Cross-cultural Ministry. (2006). Snapshots of multicultural ministry; Uniting Church in Australia. Multicultural Ministry, Crowe, C., & Yoo, S. (2000). You & I: our stories (Ser. Building bridges series, bk. 2; bk. 2). ↩︎

- Two empirical research studies support this claim. Cf. SA Synod Mission Resourcing, Mapping Intercultural Neighbourhoods in SA: CALD & Intercultural Ministry Survey 2021; Cook. (2020). On being a covenanting and multicultural church: ordinary theologians in the Uniting Church explore what it means to be church [The University of Queensland, School of Historical and Philosophical Inquiry]. ↩︎

- See footnote 14. ”Being intentionally multicultural is different from simply making a statement that a congregation will accept people whatever their cultural background. It involves working out how they can intentionally involve people of a variety of background within their worship, their decision-making and their various activities” Hughes, P. J., Bond, S., & Christian Research Association (Vic.). (2005). A handbook for cross-cultural ministry. Openbook, p. 38. ↩︎

- The term ‘cross-cultural’ describes our calling by God in Christ as to how to live our lives in respectful relationships with one another across and between cultural boundaries and divides and always under the cross of Christ, guided and empowered by the Holy Spirit. ↩︎

- The expression “intercultural” is increasingly preferred by some to “multicultural”, as it aspires to a more intentional embracing of our diversity in the Body of Christ. The Assembly uses a multicultural church interchangeably with an intercultural church – both these terms can be used to define a church that: accepts, supports, and celebrates more than one cultural group and intentionally encourages all cultural groups to engage in inter/cross-cultural relationships that respect and celebrate each culture, and shares leadership, mission and ministry between the different cultural groups. https://uniting.church/our-intercultural-church/, accessed December 2021. Cf. United Church of Canada, 2011. Defining Multicultural, Cross-cultural, and Intercultural. The United Church of Canada/L’Église Unie du Canada ↩︎

- Champion, D., & Dewerse, R. (2014). Yarta wandatha. Denise Champion, p. 60. ↩︎